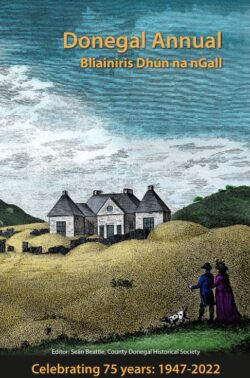

In the month of February 1888, an American visitor called William Henry Hurlbert visited Gweedore and stayed in the hotel built by Lord George Hill. He published his account of his travels in a book entitled IRELAND UNDER COERCION. The book is of interest as it provides an independent insight into life in Donegal in the 1880s following the Land War and several evictions across the county. His prose is colourful and would not be out of place in one of today’s travel guides. Hill was one of the county’s great entrepreneurs and this excerpt highlights one of his great innovations – a hotel in one of the most inaccessible districts of the county. You can still visit this hotel, now called AN CHUIRT, GWEEDORE. I called there earlier this year and and can say it is well worth a visit.

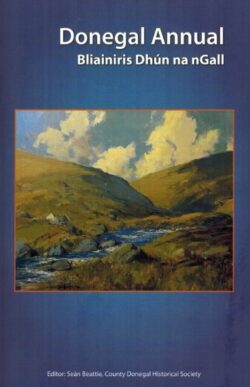

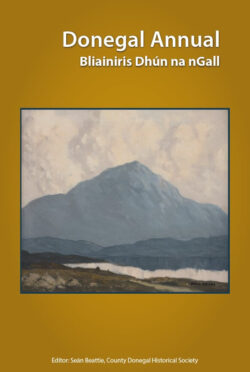

GWEEDORE, _Sunday, Feb. 5th._–A morning as soft and bright almost as

April succeeded the stormy night. Errigal lifted his bold irregular

outlines royally against an azure sky. The sunshine glinted merrily on

the swift waters of the Clady, which flows almost beneath our windows

from Dunlewy Lough to the sea. The birds were singing in the trees,

which all about our hotel make what in the West would be called an

“opening” in the wide and woodless expanse of hill and bog.

This hotel was for many years the home of Lord George Hill, who built it

in the hope of making Gweedore, what in England or Scotland it would

long ago have become, a prosperous watering-place. Now that a

battle-royal is going on between Lord George’s son and heir and the

tenants on the estate, organised by Father M’Fadden under the “Plan of

Campaign,” it is important to know something of the history of the

place.

Is this a case of the sons of the soil expropriated by an alien and

confiscating Government to enrich a ruthless invader? I was told by a

Nationalist acquaintance in Dublin that the owner of Gweedore is a near

kinsman of the Marquis of Londonderry, and that the property came to him

by inheritance under an ancient confiscation of the estates of the

O’Dounels of Tyrconnel. All of this I find is embroidery.

The “Carlisle” room, which our landlord has assigned to us, contains a

number of books, the property of the late Lord George, and ample

materials are here for making out the annals of Gweedore. Lord George,

it seems, was a posthumous son of the fourth Marquis of Downshire, and a

nephew of that Marchioness of Salisbury who was burned to death with the

west wing of Hatfield House half a century ago. He inherited nothing in

Donegal, nor was any provision made for him under his father’s will. His

elder brothers made up and settled upon him a sum of twenty thousand

pounds. He entered the Army, and being quartered for a time at

Letterkenny, shot and fished all about Donegal. He found the people here

kindly and friendly, but in a deplorable state of ignorance and of

destitution. Their holdings under sundry small proprietors were entirely

unimproved, and as their families increased, these holdings were cut up

by themselves into even smaller strips under the system known as

“rundale,”–each son as he grew up taking off a slice of the paternal

holding, putting up a hut with mud, and scratching the soil after his

own rude fashion. This custom, necessarily fatal to civilisation,

doubtless came down from the traditional times when the lands of a sept

were held in common by the sept, before the native chieftains had

converted themselves into landlords, and defeated Sir John Davies’s

attempt to convert their tribal kinsmen into peasant proprietors.

Whatever its origin, it had reduced Gweedore, or “Tullaghobegly,” fifty

years ago to barbarism. Nearly nine thousand people then dwelt here with

never a landlord among them. There was no “Coercion” in Gweedore,

neither was there a coach nor a car to be found in the whole district.

The nominal owners of the small properties into which the district was

divided knew little and cared less about them. The rents were usually

“made by the tenants,”–a step in advance, it will be seen, of the

system which the collective wisdom of Great Britain has for the last

twenty years been trying to establish in Ireland. But they were only

paid when it was convenient. An agent of one of these properties who

travelled fourteen miles one day to collect some rents gave it up and

drove back again, because the “day was too bad” for him to wander about

in the mountains on the chance of finding the tenants at home and

disposed to give him a trifle on account. On most of the properties

there were arrears of eight, ten, and twenty years’ standing.

Leave a Reply